By Nii B. Andrews

Bob Marley’s lyrics (laced with biblical references) in his 1977 roots reggae classic, Exodus, point to the importance of voluntary/involuntary movements in African history.

Some of these movements precede the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

He called for a return of diasporic Africans (Jah people) from Babylon to “the fatherland”.

Today, the diaspora is composed of many diverse groups, possibly with competing interests and visions of the future- just like those in “the fatherland”.

The diaspora presents a complex picture; it is certainly not homogeneous.

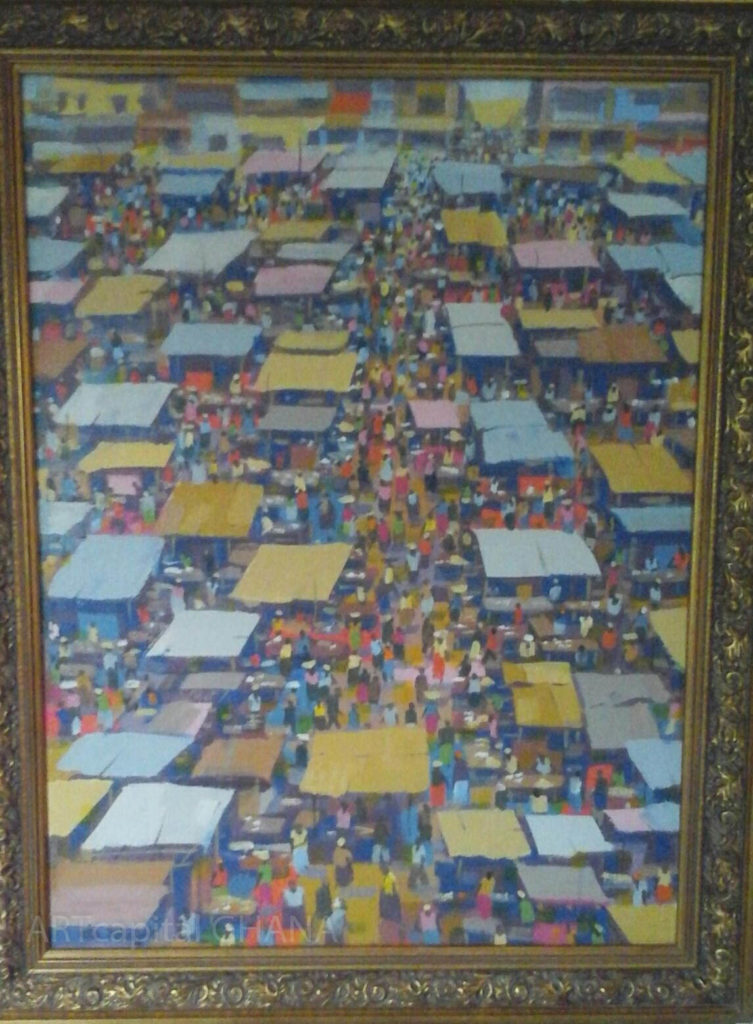

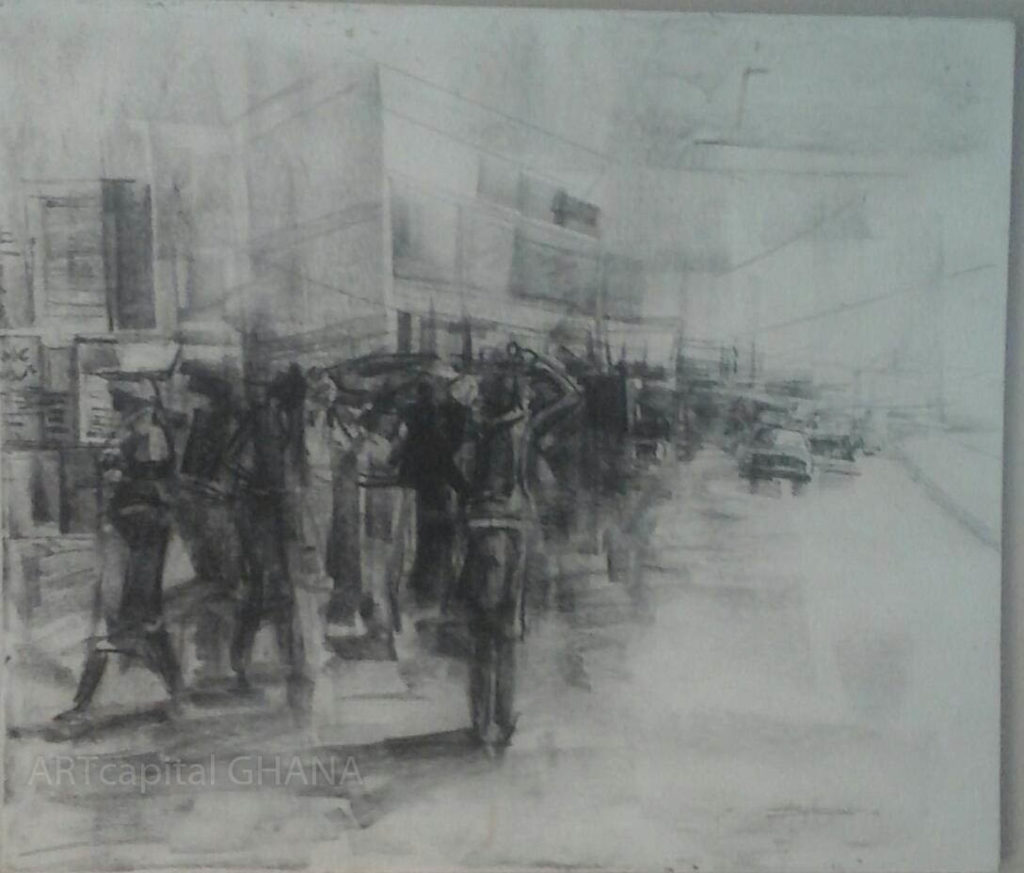

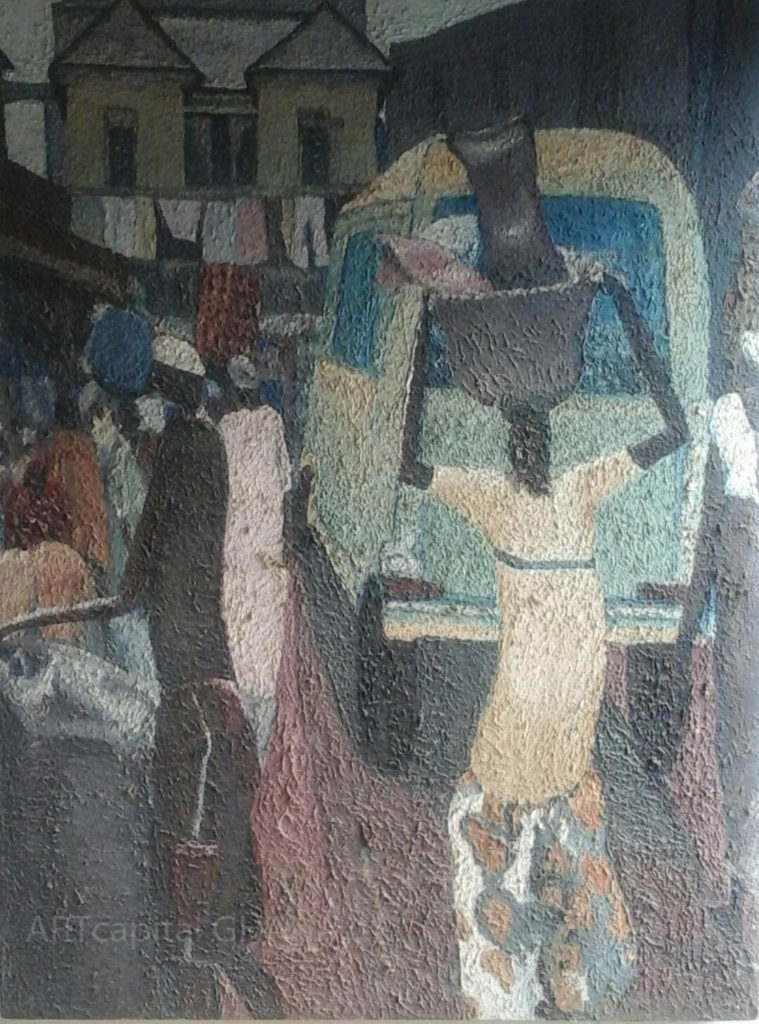

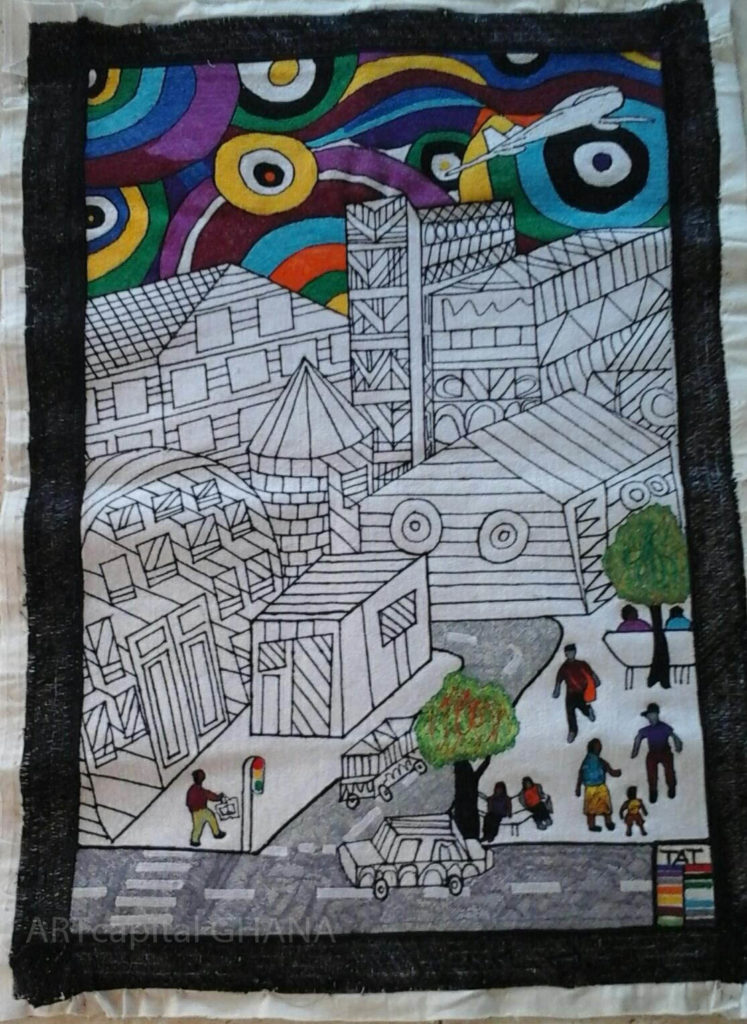

When we evaluate the works of contemporary artists of African descent, we find a constant emphasis but changing understanding of the meaning of exodus.

Currently, the contemporary African art (CAA) scene points away from an exodus of artists in one direction (away from Africa) to one of circular movement in and out of Africa.

Many examples abound.

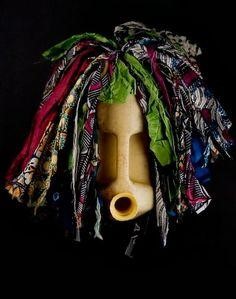

They include Kehinde Wiley (Obama’s chosen portraitist) who checked out his Ibo roots while perfecting his signature hip hop style; Owusu-Ankomah with his Adinkra ideographs; Roland Hazoumé with his classically referenced masks made from recyclable materials and the late photographer Leila Alaoui.

In the words of Stuart Hall, “the most exciting art is made by those who live simultaneously in the center and at the periphery”.

Of further importance is the influence of diasporic Africans on the market for CAA.

The most relevant diasporic groups in this regard are the middle class and the offspring of well heeled diasporic Africans.

The term that has been used (accepted at times and other times also severely critiqued) is Afropolitan.

This apparently privileged group is indebted to other communities of African descent in the diaspora (who much earlier had waged seminal battles to secure fundamental civil rights) for the ease with which they move in and out of the West.

Of course, there were groups in “the fatherland” who also won battles for self-determination.

But the Afropolitans are not all located or based in the diaspora.

A significant number are located spatially within “the fatherland” but their sensibilities and dare I say it….ethos, is markedly different and certainly more progressive than well, the non-Afropolitan regulars.

For example, the former will not burn their household refuse and engulf their neighborhoods in foul smoke on a Sunday morning or at any other time…..or do they?

These groups (the local and foreign based/ diasporic Afropolitans) are the main consumers and patrons of the CAA market.

Their connections and networks serve to project CAA and firmly place it within the global cultural matrix, especially in the West.

For now, this is the most significant driver of value in the CAA market.

When and how that will change will determine the growth and quality of the CAA market in “the fatherland”.

“When ya see Jah light. (Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha!)”